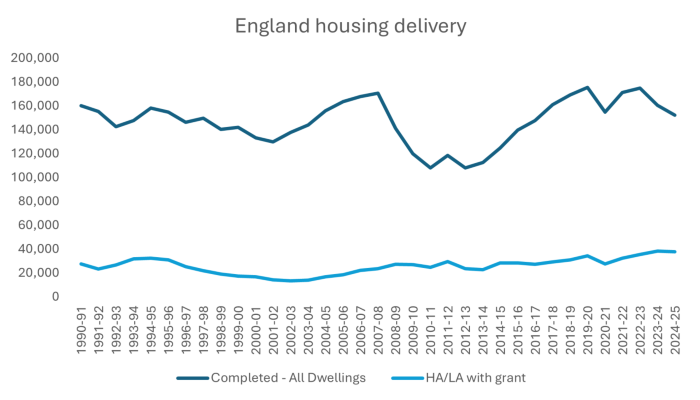

The chart shows English housing delivery since 1990. At no point in the past 35 years has housing delivery been anywhere near the 300,000 target. The 10 year average since 2015 was around 155,000 homes per year. That means the target requires is an additional 145,000 homes per year of all tenures to be built.

Do we really expect to hit the target? There is broad consensus within the housing sector that this target is unrealistic.

It is a commendable goal, but the challenges are daunting. Financial resources are understandably being diverted from development towards addressing building and fire safety, and remedying damp and mould issues. As we deal with the lessons of Grenfell and prepare for new Decent Homes Standards, housing associations are having to make a hard choice between building new homes or fixing existing stock.

Rising construction costs and borrowing rates also make the viability of new housing schemes marginal at best. During the past 10 years the average construction cost in England has risen by over 50%. Meaning that, on average, a 3 bedroom home that might have cost around £170,000 (excluding fees and finance costs) could now cost over £260,000. Higher borrowing costs over that time also means lower capitalised value for rented homes, since the ‘value’ of rented properties is calculated by capitalising rents over the letting period.

Land Cost: The Constraint That Shapes Everything

The cost and availability of land is one of the most significant challenges facing developing RPs. It is often the largest component of development costs, and this cost rises sharply when planning permission is given. M3 Development Consultant, Neil Clements, points out that bare agricultural land in England can be worth around £10,000 per acre, subject to regional variation. The same land with residential planning permission can be worth £300,000 per acre in the South West and well over £1 million per acre in the South East. With land bought for open market residential development, rather than affordable housing, the uplift can be even greater. In practice, securing planning permission can increase land value by more than thirty times. Landowners cannot realistically be expected to discount land for registered providers when the same site is viable for open-market development.

Section 106: The Hidden Subsidy Under Pressure

Section 106 Agreements are one of the mechanisms used to counter the impact of rising land costs, referring to S106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. These agreements allow a local authority to impose public service obligations on a developer in order to get planning permission. They specify the proportion of homes that need to be affordable, and the levels needed to calculate the affordable and social rent for those properties. The affordable homes (other than discounted sale homes) will be sold to registered providers (RPs) of social housing. These RPs include both traditional and for-profit providers.

S106 agreements create a huge hidden subsidy for affordable housing. It doesn’t appear in government budgets, but it’s built into the way land is valued. When a developer considers a site, they start by calculating how much it will cost them to deliver the affordable homes. They then knock that cost off the price they can offer for the land. In effect, S106 “taxes” land value at source, before a spade even hits the ground.

Developers also have to estimate how much RPs will pay for the completed homes, which is always much lower than the cost of building them. The difference becomes the subsidy, absorbed through the land price. And it is not small. Although there are no up-to-date official records, a 2020 MCHLG report shows that, of around £7billion of tax receipts related to local authority planning obligations, around two thirds supported affordable housing.

Most of this probably went into Shared Ownership and Affordable Rent, because Social Rent needs far more subsidy and would reduce the number of homes delivered. While S106 underpins much of England’s affordable housing supply, delivery through these agreements is faltering as land bids decline and RPs scale back development.

The gap between approved and contracted schemes is widening, with thousands of affordable homes approved in principle but stuck in limbo. A 2024 Home Builders Federation survey found that over 17,000 S106 affordable homes with detailed planning consent remained uncontracted, delaying progress on 139 sites across England. A 2025 survey by Knight Frank reported that 80% of developers across England struggle to find RPs to take on their affordable homes, and 40% cannot find a single provider. Inside Housing’s 2025 Biggest Builders survey confirmed the downward trend. S106 homes made up 42% of housing association completions two years ago, fell to 37% last year, and are projected to fall to 30% this year. In real terms, that’s a fall from around 14,700 S106 homes to just 10,000 in three years.

Why Deals Stall Before They Reach Contract

Rising build costs and tighter budgets also mean RPs are far more cautious before committing. Especially while they are also dealing with the cost of fire safety works, damp and mould investment, and new regulatory pressures. Smaller housing associations are also shifting focus to building their own homes with grant, giving them more control over quality and timing. In some areas, there just aren’t enough registered providers to take schemes on. Put together, these pressures mean more S106 homes getting planning permission, but far fewer reaching contract stage. This leaves developers with units they cannot place and councils with affordable housing targets stuck on paper rather than on site.

Housing associations also say many S106 homes have become too expensive, driven up by years of bidding wars with for-profit RPs. Even when the numbers work, the negotiations can be painfully complex. Agreeing specifications, layouts, handover standards, viability assumptions, and risk allocations can take months. Some deals simply fall over under the weight of it all. The appraisals behind those prices also often don’t stack up once finances are reviewed in detail.

An October 2025 report by Parliament’s housing committee made a number of recommendations to address the issues with S106. It recommends standardised S106 templates, so negotiations can focus on on-site issues rather than legal wordings, and a statutory dispute resolution process to stop viable schemes getting stuck in deadlock. The report also highlights the lack of up-to-date land value data, warning that appraisals are being built on outdated assumptions that no longer reflect market conditions. Transparent land values, clear and consistent local affordable housing targets, and better resourced planning teams would reduce delays, improve trust and reduce the number of approved schemes that never see the light of day. The recommendations reinforce a simple message: clarity, consistence and credible evidence at the start of the process matter if S106 is going to deliver at scale.

It ultimately comes back to confidence at the number at the start of the scheme. Accurate early modelling helps RPs decide whether a site really works for them, helps developers avoid pricing based on optimism, and gives councils evidence they can trust when signing off a scheme. Schemes that move quickly are the ones where assumptions on valuation, rent, costs, and land are visible, agreed early and defensible. This is the moment for organisations to step back and reassess how early-stage decisions are made. Are their current appraisal approaches truly supporting negotiation and delivery? If confidence in the numbers is missing at the start, it rarely appears later.

The real test of the 1.5 million-homes ambition is not planning consent. It is whether land costs and Section 106 obligations can be resolved before deals collapse. Until that happens, targets will continue to outpace delivery.

About the Author

Craig Oosthuizen is Head of Commercial at M3 Housing, formed in 2004 by experienced practitioners to provide a unique combination of expertise in housing appraisal and development, surveying and software design. Craig has over a decade's worth of experience in housing policy and property technology.